There are many treatment options for perinatal depression, which include both postpartum depression or postnatal depression presentation and symptoms. It is really important to start with this message and reassure expectant or new parents there are effective ways to treat depression in the perinatal period. To be helpful, below we will discuss in further detail common treatment options and look at the different symptoms of postpartum depression and/or anxiety.

Even for professionals working in the perinatal mental health space, there are a range of different labels used to described depression following birth, which can be confusing to understand. Postpartum depression is often a term used in medical or diagnostic settings to describe parental depression, but has historically only applied to a short period post birth, being up to 4 weeks. Confusingly, postnatal depression has historically referred to depression developing in the period of up to 6-12 weeks post birth or including the ‘fourth trimester’.

Despite these origins, postpartum depression and postnatal depression are often used interchangeably and used to describe longer periods of time following birth. In contrast, perinatal depression covers a longer period of time, where depression occurs any time during pregnancy or following the birth for a period of up to one year.

To try to make this blog less confusing, we will use the term postnatal depression to describe depression which develops after birth for up to a year post birth. This is because for our purpose, we feel it is most important to capture parents who develop depression both during and after the fourth trimester and we also want to encourage new parents in this phase to be included in screening and support seeking as needed.

How do I know if I have postnatal depression?

You’ve just had a baby – what a roller coaster of emotions that was! It is normal to have feelings of overwhelm, sadness, crying spells, mood swings, anxiety and difficulty falling or staying asleep after the birth of your baby, and these experiences are known as symptoms of the ‘baby blues’. Emotions experienced during this baby blue period are likely to be different for every birthing person, so it can difficult to notice symptoms and understand these. The baby blues period is known to occur for a short period after giving birth.

It is difficult to know whether you are struggling with developing postnatal depression symptoms, are experiencing postnatal depression or other mental health problems or whether it’s the normal (although different for everybody) baby blues. So how do you know whether you are experiencing baby blues or if you are at increased risk to develop postnatal depression? Symptoms of postnatal depression are not something you need to navigate yourself and it is best to reach out for support to discuss your concerns if you are unsure if this is baby blues, worried you may be struggling, or even may be developing postnatal depression.

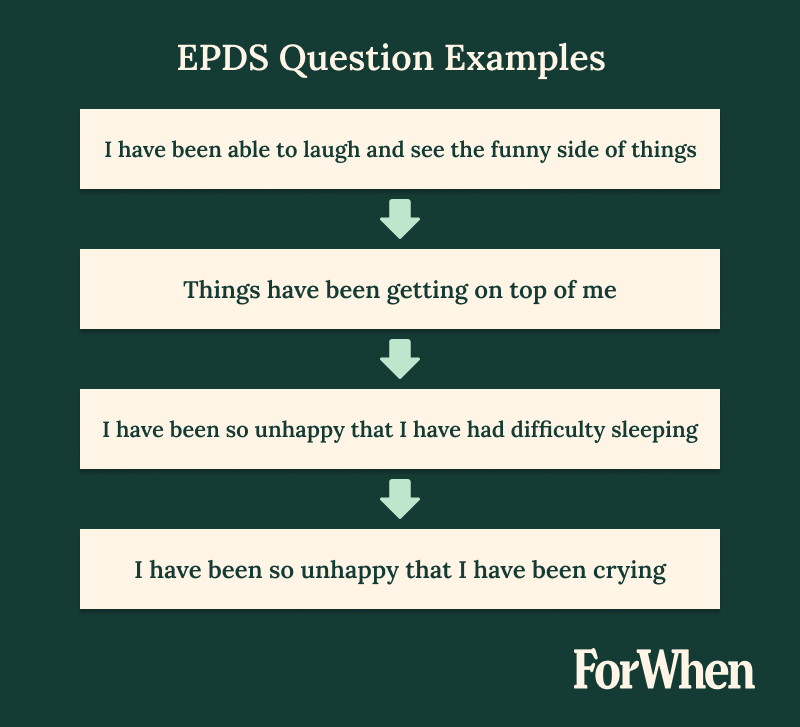

Discussing concerns or possible symptoms of postnatal depression with a professional – for example with your General Practitioner or health visitor, such as a Child and Family Health Nurse, can lead to assessment and screening for postnatal depression or anxiety. More importantly, gaining an understanding of clinical symptoms of postnatal depression or anxiety can pave the way for receiving appropriate support to manage and treat it. Using a screening tool such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) can indicate the presence of postnatal depression or postnatal anxiety or whether you may be at risk of developing postnatal depression. See below for more information on this screening tool.

Screening for postnatal depression and postnatal anxiety is important as a new baby can bring all sorts of emotions to the surface, as mentioned with the baby blues. Alongside distinguishing postnatal depression screening from baby blues, it is important to screen for other physical health problems, as our hormones may not be back to normal after birth. It can take time for these hormones to be balanced again and return to pre pregnancy levels. So, attending the GP to get a blood test to check the levels for example of thyroid hormone is important, as thyroid dysfunction comes with symptoms which are similar to postnatal depression.

As per the example above, it is significant to include thorough screening for physical symptoms for women with postnatal depression or who are at risk for developing postnatal depression, to understand whether medical treatment may be required, other treatments are suitable or identify psychological treatments appropriate for postnatal depression. Untreated physical conditions can also increase the risk of postnatal depression. It is important to also consider external influences for families, such as relationship problems, other stressful life events or risk factors; such as antenatal anxiety or depression, as these may all be contributing to postnatal baby blues.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

The EPDS is a 10 question multiple choice screening tool. Both birth and non-birth parents can and should complete the tool. The tool can be used in pregnancy as well as postnatally, by a professional such as a health visitor, to screen for perinatal depression and anxiety. The tool should be completed more than once throughout during the perinatal period. Each question has the same rating, and a total score is calculated to determine the likelihood of postnatal depression. Questions in the tool relate to feelings or symptoms experienced over the past seven days. Further follow up and assessment is required when a score is above 13 or if question 10 has a rating above 0.

It’s important to know that the EPDS is not a diagnostic tool for postnatal depression, but is rather a tool to screen parents and identify potential postnatal depression symptoms which is more accessible as it can be completed by a health visitor/professional or non-specialist professional. If postnatal depression is indicated by this tool, there is likely a need for further assessment and if there is a subsequent postnatal depression diagnosis, suitable treatment by an appropriate professional can commence

The EPDS is available in multiple languages, however there must be consideration for cultural differences and barriers to using and interpreting this tool with different populations. Barriers might include understanding of language, recognition of postnatal depression, stigma in community and trusting of mainstream services.

Key Highlight

It’s crucial to understand that the EPDS is not a diagnostic tool for postnatal depression. Rather, it screens parents and identifies potential symptoms. It’s an easily accessible tool which can be completed by a health visitor, non-specialist professional or a qualified healthcare provider.

How is postnatal depression treated?

Postnatal depression treatments vary depending on the parent’s mental and physical health history, current symptoms of postnatal depression or depressive episodes, experience of giving birth, psychosocial factors during the postnatal period and also what the person’s personal preferences for engaging with support are. These factors may all impact the depression screening process, which is the step that needs to occur before treatment for postnatal depression.

Some parents may also prefer alternate or less formal options to supplement their treatment journey for postnatal depression, such as a support group or more practical types of help such as parenting programs, peer support or sleep support services. We will talk more about some of these other options later in this blog to give more of an idea.

Postnatal anxiety

After having a baby, postnatal anxiety has been found to be as common as postnatal depression. This may include excessive worry about whether you are doing the ‘right’ thing, or worrying whether baby is ok. When this worry is daily, you are ruminating on negative thoughts or even having panic attacks which impact you physically, professional assessment and guidance is required. Psychological treatment such as medication and therapy can help you understand the triggers of your anxiety, reduce severity of symptoms and help you develop tools and confidence to manage anxiety.

Anxiety and sleep (and often the case with postnatal depression and sleep) are very much related. Trouble sleeping is common after you have a baby as you will need to wake and feed your baby frequently and help to resettle your baby to sleep as they can’t manage this alone. Signs of insomnia include ongoing issues with struggling to fall asleep, struggling to stay asleep or being unable to sleep even when your baby is sleeping. Insomnia or trouble sleeping can exacerbate your anxiety, as well as postnatal depression and other disorders. Sometimes insomnia can be the first noticeable symptom of postnatal depression or other psychological issues. If insomnia and high anxiety is left untreated this can lead to more severe postnatal depression. It is important to seek support from your GP as a starting point, if you feel these sleep issues apply to you.

Key Highlight

Untreated insomnia and high anxiety can worsen postnatal depression. Seeking support from your GP is crucial if you’re experiencing sleep issues. It’s a good starting point to address mental health concerns.

Baby blues

Managing the care of a new baby, looking after yourself and still maintaining or contributing to the household can be a lot in the adjustment period after birth – the prime time for baby blues. There are small things you can prioritise to assist with managing those early baby blues and hormonal changes.

The normal mood swings and lack of sleep can be managed by prioritising self-care such as making sure you eat, sleep (if possible), shower, asking for help and creating time to still do things you enjoy in this phase of adjusting to being a new parent.

Baby blues don’t last long after having your new baby. It is when feelings of extreme sadness, mood swings, severe agitation, tearfulness or negative thinking continues, the need for a further assessment to screen for postnatal depression is a must.

Postnatal depression

Psychological assessment and treatment plays a very important role in the recovery of perinatal depression. Finding a mental health provider who provides assessment, therapy and or counselling in the perinatal space can make such a difference exploring whether issues are related to mild, more severe or chronic postnatal depression, adjustment to parenthood, family of origin, relationship issues, bonding issues with baby and of course those feelings of anxiety and depression. A psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker or counsellor can assist with these psychological treatments, using a range of different therapies. These professionals are also able to use other forms of screening tools to understand postnatal depression to form a diagnosis and/or treatment plan, which can depend on the type of professional you see.

Alongside psychological treatments you can be prescribed medication for the treatment of perinatal depression. Antidepressant medications are the most frequently used medical treatment, which are most likely to be selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and can assist with reducing severe mood swings. However, other treatments or medication may be more appropriate depending on diagnosis. Antidepressant medication can also assist with lowering anxiety and stabilising mood swings. Other forms of medication may be beneficial when symptoms of postnatal depression and anxiety are more severe.

Antidepressant medicines may not be suitable or chosen by everyone and some parents may prefer to engage in options such as psychotherapy or talk therapy, with many of these interventions well researched and regarded as effective psychological treatment for treating postnatal depression.

Birth parents or women with postnatal depression may require a more medical or combined approach to treating postnatal depression, as there may be physical health symptoms after giving birth to address as well. This may require interventions such as a blood test for thyroid function and subsequent hormone therapy, if you remember our previous example of thyroid dysfunction and this is in a more severe form. Treatment pathways for this type of issue will depend on severity, with hormone therapy reserved for more major symptoms.

Key Highlight

A proactive approach to seeking help can make such a difference exploring whether issues are related to mild, more severe or chronic and connect you to the pathway for recovery.

Postnatal psychosis

Postnatal psychosis can be a severe illness with serious consequences if it remains untreated. While not a common diagnosis, it is important to recognise postnatal psychosis requires specialist assistance to make sure that both you as the parent and your baby remain safe.

Being diagnosed with postnatal depression does not mean you will develop postnatal psychosis. Factors which may increase risk are previously diagnosed postnatal psychosis, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, or a family history of psychological illness – particularly postnatal psychosis.

If you are worried you may be having irrational or thoughts that scare you, have risk factors for postnatal psychosis (such as a previous diagnosis of postnatal psychosis) or someone close to you is concerned about changes to your behaviour, you should reach out to a GP or a perinatal mental health service for support. There are urgent crisis numbers that can be called, such as Crisis Assessment Teams, who are usually open 24/7 depending on which state you are in.

Postnatal risk

Suicidal ideation or thoughts of self-harm can be present for a range of mental conditions in the postnatal period, including for postnatal depression. It is important to let someone know if you are having these thoughts as there are many pathways to getting help to support you. Suicidal thoughts may be an indicator of risk that you or your baby are not safe, so it is crucial you reach out and talk to someone if this is occurring for you. There are various supports available for you to call including your GP, Lifeline, PANDA or ForWhen.

*More detailed discussion of treatments for postnatal depression is provided below.

Therapies

As noted previously, there are a range of different professionals who can provide different types of assessment, therapy and intervention where there are psychological issues or postnatal depression. GPs are a starting point for getting a referral to see a specialist and can assist in directing with which type might suit your needs. There are specialists working both in our public hospital systems in Australia, as well as in private settings – although these often come with an out of pocket cost and not usually completely covered under Medicare.

Psychiatrists have the ability to also prescribe medication, as they come from a more medical background in terms of qualifications, as well as providing psychological therapy. Psychologists and psychiatrists also specialise in diagnosis, whereas counsellors, psychotherapists or accredited mental health social workers or nurses may be more likely to provide intervention or psychological treatment support.

Alternate options for therapy may be more appropriate for your circumstances, with some states offering ‘mother baby units’ through public and private hospitals, which are residential treatment programs for postnatal depression, as well as other psychological diagnoses. These provide a short term but intensive option where you can stay with your baby to receive support while you adjust to being a parent and your emotional health or postnatal depression is treated.

Other outpatient public hospital support options for postnatal depression may include programs which focus on adult, infant or perinatal or infant psychological interventions, which aim to treat parent or infant functioning and wellbeing, relationship building, bonding and promote security in the attachment relationship.

Community options may include a specific type of support group and there are many which focus on the adjustment period of becoming a parent, as well as promoting your relationship with your baby. Options might include programs such as circle of security, which promotes the relationship or what we describe as the infant-parent attachment. While groups such as this are not targeted at treating postnatal depression, they may contribute to overall psychological recovery.

It is also important to remember the significance of partner relationships during the perinatal period, as this is statistically the most difficult period for a relationship. Where issues arise in partner relationships, it may be appropriate to consider an intervention such as couples or family therapy to address this. This may be appropriate in a case where one parent has been diagnosed with postnatal depression, as this may assist with communication and how parents can support one another through these issues.

Key Highlight

Psychiatrists, with a medical background, can prescribe medication and provide psychological therapy. They specialise in diagnosis. Counsellors, psychotherapists, and accredited mental health professionals provide intervention and psychological support.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy or ‘talk therapy’ refers to a broad approach used by a range of treating professionals, including psychologists, psychiatrists, counsellors, psychotherapists and allied health workers. There are various types of psychotherapy which are commonly used to treat postnatal depression. The particular approach may depend on the type of health professional providing treatment and individual needs. We will explore a few commonly used forms of psychotherapy further below, as well as some alternate types of treatment for postnatal depression.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

As mentioned, there is a lot of evidence for CBT as an effective treatment option for postnatal depression. This is usually the case for mild-moderate postnatal depression and is common because it is a treatment than can usually occur in a limited number of sessions, and Medicare funds up to 10 sessions currently with a registered provider – like a psychologist or mental health social worker.

CBT is a talking therapy or type of psychotherapy which provides a structured intervention with the aim being to change problematic cognitions or thought patterns and subsequent problematic behaviours. CBT is most often used to treat postnatal depression (and anxiety) and works to build understanding about how thoughts, feelings, physical responses and behaviours are related and so underlying negative thought patterns can cause problems in how you feel, continue to think and behave. CBT focuses on current issues rather than resolving past issues and provides a step by step approach to working to reduce negative thoughts with the aim this will reduce negative feelings and way of acting or coping.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

Electroconvulsive therapy is used when other forms of therapy have not aided in the healing of the mental illness, including for postnatal depression or chronic depression. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a procedure, done under general anesthesia, in which small electric currents are passed through the brain, intentionally triggering a brief seizure. ECT seems to cause changes in brain chemistry that can quickly reverse symptoms of certain psychological conditions.

This explanation and indeed treatment option may alarm you and bring to mind monstrosities of the previous century which occurred in the name of psychiatric treatment (well before the time when postnatal depression was a recognised diagnosis!) – however modern techniques are considered safe and effective for more severe cases. It is important to assess benefits against side affects for this treatment and ensure that this method is used when deemed the best opportunity for positive psychological outcomes and an improved quality of life.

The following mental illnesses can be treated by using ECT; severe depression (including antenatal and postnatal depression), catatonia, forms of mania and schizophrenia. ECT can be used when a quicker intervention may be required, such as during pregnancy. Side effects from the treatment, which are usually temporarily occurring on the day of treatment, include headache, nausea, fatigue, confusion and slight memory loss which can last anywhere between minutes up to a few hours. Other side effects included are risks with having a general anesthesia.

Interpersonal therapy (IPT)

Interpersonal therapy is a type of psychotherapy which usually occurs over a limited number of sessions, similar to CBT and resulting in this option being accessible in terms of the number of sessions which Medicare provides a rebate for. IPT also focusses on managing symptoms of mental illness as with CBT, but it is different as it has an attachment-focussed approach. When we talk about attachment with parents we are thinking about the relationship quality, which is understood based on a wealth of evidence stemming from attachment theory. Because this attachment relationship is closely linked to psychological health (both parent and infant), IPT is considered an appropriate intervention for managing postnatal depression.

Infant Mental Health Approach

Infant mental health has origins in attachment theory, psychodynamic theory and developmental psychology. When thinking about perinatal psychological health or postnatal depression, it is really important to remember the psychological wellbeing of the infant. As suggested with IPT, the infant-parent relationship is a key ingredient to ensuring emotional wellbeing for both baby and yourself as the parent. With your baby being so dependent on you from birth, their emotional wellbeing can be closely linked yours, but with this being said, it is important to remember your baby is also an individual with their own emotional experience separate to yours. When an infant is experiencing psychological distress, this may impact their physical health and growth and things like their sleep and feeding routine.

Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT)

There is growing evidence to support the use of DBT where there are a range of psychological challenges, including during the perinatal period, including where there may be issues with postnatal depression. Where this approach was initially created as a treatment for people with Personality Disorder traits or diagnoses, it is increasingly being found to be effective in treating other symptoms or diagnoses where there is emotional dysfunction. DBT includes the learning of mindfulness skills to manage emotional distress and these can be particularly helpful strategies to use when transitioning into the role of parenthood. There is some more recent research supporting benefits of using DBT during the perinatal period, given the significant emotional changes and distress often experienced during this time frame.

Summary of various therapy options

There is no one approach that will be effective for treating every person experiencing postnatal depression – one size does not fit all and intervention should be based on your unique and personal circumstances. For the purpose of demonstrating this, we have tried to share a taste of a few of the more common types of therapeutic approaches used perinatally, but there are many more options.

Medications

Alongside therapy there may be a need for medication to treat postnatal depression and anxiety. Antidepressant medications are commonly prescribed to help assist in the treatment of postnatal depression. There are many types of antidepressant medication but the two commonly prescribed will be discussed below. Just to note there are other forms of medication that can be used to treat postnatal depression and anxiety. Also, there are other factors to consider when a medical professional will prescribe medication such as pre-existing physical and psychological issues, current depressive symptoms and whether you are breastfeeding your infant, as this may have an impact via consuming breast milk.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

SSRI’s assist in treating depression and anxiety symptoms by increasing the level of serotonin in the brain by inhibiting the uptake into the nerves. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter (chemical messenger) that sends signals between nerve cells in the body. The main function of serotonin is to stabilise your mood, be the communicator between the brain and the nerve cells and also has an effect on the digestive system and sleep cycles. By taking a SSRI daily some reduction in symptoms may be noticed within one to two weeks; however, it may take six to eight weeks of treatment before the full effects are seen. There are fewer side effects with taking a SSRI as the body adjusts to the medication and this is why it is commonly prescribed.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants were one of the first antidepressant medications made. They are known to be a second line choice to a SSRI medication and usually prescribed for postnatal depression when a SSRI has not been effective in treating symptoms or side effects have remained. Tricyclic antidepressants work similarly to SSRIs by blocking the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine (however are not selective in which neurotransmitters they block the reuptake of) allowing more of these neurotransmitters to be available for the brain. In layman’s terms, this assists with stabilising mood and usually has a good effect on digestion and sleep cycles. These antidepressants can be prescribed to treat pain, obsessive compulsive disorders, and sometimes panic disorder. In saying all of this, side effects which can be more common include constipation, weight gain and sedation.

Summary of medication

It is important to remember to seek medical advice for your own individual health needs. Medication will work very differently across people, so something that works for you may not work for someone else, even if your diagnosis of postnatal depression is the same. Further, if you are prescribed a medication which does not work out for you, this does not mean that an alternate medication won’t work. We have hugely different biology as humans and as a result, the effectiveness of medication will not be one size fits all.

Diagnosis is helpful to guide types of medication that might work for certain people. For example, someone seeking to treat postnatal depression compared to someone looking to treat bipolar disorder will likely require very different medication. This is interesting when you consider that bipolar disorder includes depressive episodes as part of the diagnosis, so is similar in this way to postnatal depression. Appropriate medication will also also depend on whether your illness is a mild or more severe form of psychological distress or postnatal depression, which is why accurate assessment of your symptoms by the right professional is crucial.

Support groups

Engaging with a support group can provide the emotional support that a new parent needs. This is not for everyone and not just for parents experiencing postnatal depression. Some parent are keen to get out and meet new people in the parenting sphere and some prefer one on one interactions – which is completely your choice! Support groups are offered through your local council or may also be offered through local community services. Maternal and Child Health nurses often arrange a group for new parents, to assist connecting local new parents together and also provide another avenue for support and education.

Meeting and speaking about the experience of bringing home a new baby can bring reassurance that the struggles one feels may be felt by another. A new parent may feel isolated at home and attending these support groups may provide a safe, friendly environment to attend regularly. While saying this, parent experiences can be incredibly different, so it is important to have realistic expectations that your journey may not look the same as that of another new parent, even if you have postnatal depression in common.

Key Highlight

Postnatal experiences can vary greatly, so it’s essential to have realistic expectations. Your journey may not mirror that of another parent, even if you share postnatal depression.

Risks of untreated postnatal depression

* I want to add a disclaimer that this paragraph talks about self-harm and suicide. If this is likely to distress you significantly, please jump to the next heading.

There are significant risks associated with not seeking treatment for postnatal depression. This is because we consider the wellbeing not only of the parent to be compromised, but also the wellbeing of the baby is at risk. Infants are very dependent on their caregiver to meet all of their needs, so when their caregiver is unable to meet these needs, there are likely to be impacts to the infant’s development, health and own emotional health – as we have discussed, infant mental health and wellbeing is real and needs to be promoted. Having said this, I want to be clear there is no perfect parent who meets their babies needs accurately every time and this is ok! We believe in ‘good enough’ parents and not perfect parents. However if you are in such psychological distress than you cannot function daily as an adult, then it is likely you are going to struggle to care for another very small and vulnerable human baby.

The risk of untreated postnatal depression also include your own safety as a parent. If you remain in psychological distress for an extended period without getting help, and it will likely continue to get worse over time untreated, you are likely to experience issues not only with your emotional wellbeing, but also your physical wellbeing. Untreated postnatal depression is likely to have negative impacts on your family relationships, how you see yourself and your identity and cloud your experience of being a parent. You may feel increasingly hopeless, worthless and unbearably sad, which may lead to unhelpful coping strategies like avoidance; using substances, withdrawing from life or enjoyable activities or self-harm or thoughts/attempts at suicide as a means to escape.

A really important message from us at the ForWhen Helpline is that if you are struggling, even if you’re not sure exactly what is going on, whether it is postnatal depression or something else, help is available so please reach out. It is better to find out your postnatal depression symptoms are mild (and treat them early for better, quicker outcomes) than let these continue to get worse. It’s important to know through seeking the right support you will get better.

Seeking professional help

As mentioned earlier, there are crisis services you can call (or someone can call on your behalf) in the case of a psychiatric emergency. These services may be referred to as CATT, Acute Community Intervention, Mental Health Triage or Mental Health Emergency Response line, depending on which state or territory you are in. If you are uncertain about exactly what crisis options there are in your local area, you can also call emergency services or 000 and be directed from there. We hope that by sharing information about early warning signs to look out for and options for who to contact before it gets to a critical stage we can reduce the number of parents who get to this stage, but sometimes urgent help is needed and we can direct you to it.

A mental health professional able to treat postnatal depression includes a range of different workers who have experience and qualifications specialised in this area. Many of these have been previously mentioned. Your GP is a great starting point when seeking support, however it’s important to understand that GPs are general in their role and may not have all of the answers, in terms of diagnosis and treatment for mental illness. A GP can provide a Mental Health Care Plan, which is required to receive Medicare rebates for psychological support. While the number of sessions rebated increased during the pandemic, it has since returned to a rebate for 10 sessions annually.

It is also helpful to note that even with the Medicare rebate, if you are seeking a professional outside of a public hospital (which often have long wait times) or a community service, there is likely to be a gap fee which could between $40- 140 per session. This is higher for psychiatry services. There are psychological service options through some Universities which may be cheaper, but your therapist may be in training; such as a ‘provisional psychologist’. There are some perinatal psychology options which are completely bulk billed – if you would like to know more reach out to a service like ForWhen Helpline and we can direct you.

If you have private health insurance, you may also be able to access financial support to pay for psychological interventions. What is included will depend on your level of cover; with extras only cover being more limited than comprehensive hospital cover. If you are thinking you would like to find out more about what your health insurer provides, it may be worth reaching out to them and asking.

Outcomes from seeking professional help

As discussed already, appropriate treatment for postnatal depression will differ between people and can only be decided through your preferences, what you are able and willing to access and a thorough assessment of your needs by a trained professional. Your treatment journey may include some trial and error for this reason, so it might be helpful to prepare yourself that the first option you try may not be the best option for you. It is because of such varied professional support options that services like ForWhen Helpline have been created, to assist parents as a starting point where there are concerns, such as indicators for postnatal depression, with navigating this system and finding the most suitable help.

Outcomes are more positive for parents diagnosed with depression if this is recognised and treated early. This means that there is a good chance you will make a full recovery if these symptoms are picked up and appropriate supports are put in place. This is all the more reason to seek support early on, as more than likely, there are effective treatments that can help you to feel better. Treating postnatal depression can not only improve the quality of your life as the parent experiencing this but is likely to benefit the whole family moving forward into the future.

There are many supports available for you, including the ForWhen Helpline (1300 24 23 22) who can assist in connecting you to the right service, at the right time.

Frequently Asked Questions

We’ve included some frequently asked questions about postnatal depression treatment, but if you have more after reading this blog, please reach out to us with these at ForWhen.

This is a loaded question and will depend on your personal circumstances. What I will say with absolute confidence is that doing nothing will not be helpful and could very well be dangerous. For some people psychotherapy may be useful and this may be accessible with the Medicare rebated sessions. For some people medication may be key in the recovery process, sometimes alongside therapy. Sometimes more prolonged or severe postnatal depression may not respond to either of these treatments of a combination of and might require an alternative such as ECT.

It is important to understand that developing postnatal depression is not necessarily within your control, although there may be lifestyle choices you can make which contribute to promoting overall mental and physical health. It may be important to understand whether there are risk factors that might make this more likely, such as previous mental health issues or difficult life circumstances and keep in mind whether your experience is more common baby blues or the potential for postnatal depression. If you have concerns about how you are feeling, please reach out and talk with someone about this and if needed, reach out for professional support.

We’ve talked about the baby blues and how common mood issues are after birth – whether low mood, mood swings or bouts of anger and frustration. Our first advice? Be kind to yourself! You have just physically carried and brought another human into the world and there are going to be impacts for your physically, mentally and emotionally – this is ok, it is when these become disruptive and ongoing that you may need extra help. It is crucial that you ask for support when you can.

Most people have heard the old African proverb: it takes a village to raise a child, but the way we live in Australia mostly in modern times does not often reflect a village. Ask for help from your partner if you have one, your extended family or friends if they are available or even professional services. You don’t have to, and shouldn’t, do this alone. A part of asking for support may be taking some snippets of time for yourself. Try to eat well, get sleep when you can, take a shower, go for a walk or reach out to a friend. If mindfulness, meditation or stretching are your jam, make time for these, even if this is only brief.

It is generally considered safe for women with postnatal depression to use certain types of antidepressant medication when breastfeeding- however, remember all medication is not equal, some are not safe and various medication may have a different impact on the individual, so this needs to be discussed with your GP or a psychiatrist. This is to ensure that nothing harmful to your baby is passed through breast milk. We recommend asking your medication prescriber this to o make sure everyone is safe.

The short answer is yes, however nothing is guaranteed. Having a history of mental health illness can put you at increased risk of feeling anxious or depressed in pregnancy and after the birth of your baby. If you’ve had this previous experience, you may be more likely to recognise if things deteriorate and this is the step required before reaching out for help.

It is helpful to note that antenatal depression or anxiety can indicate increased risk for postnatal depression, so it’s important these are screened for during pregnancy. There are certain diagnoses, such as bipolar disorder, which require specialised oversight perinatally as there can be associated risks, so it is important to be transparent about your psychological history.